In the aftermath of 9/11, the bread and butter of the

defense industry shifted in many ways from focusing on big-ticket Cold War

items like tanks and fighter jets to the world of counterterrorism and

counterinsurgency. With this new paradigm came waves and waves of

self-appointed experts, clueless academics, and hucksters trying to sell crap

to the Department of Defense. This trend continues to this day, although it has

been shifting into the even more nebulous area of cybersecurity, which is even

better for contractors given that the 60-year-old men who run the Pentagon

don’t know anything about computers. The situation is so bad in the Department

of Defense that when you come across an “expert” who dubs themselves a

COINista, you should run, not walk, away. These folks are the

reason why we are fighting the same war today that we were fighting in

Afghanistan 16 years ago.

One person who I always appreciated for having an

actual track record of success is Eeben Barlow.

Having served in the South African Defense Forces as a sapper in the Infantry

and Special Operations, Barlow went on to found a private military company

called Executive Outcomes. EO beat back UNITA in Angola for the

democratically elected government before driving the barbarous

Revolutionary United Front to their knees in Sierra Leone. Today, Barlow

serves as the chairman of STTEP, a PMC that took the fight directly

to Boko Haram.

Oddly, the United States government puts pressure on the host governments to

remove Barlow’s people just as they begin experiencing success in

defeating anti-government forces.

Using his background in counterinsurgency and

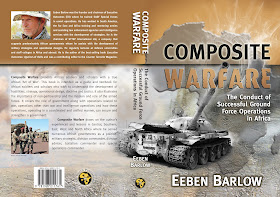

irregular warfare, Barlow has recently written a book titled “Composite Warfare,” and it is the go-to manual for warfare in

Africa, written by a man who has experienced it. Barlow emphasizes

an Africa-centric approach that eschews the over-philosophizing of

political scientists, doctrine writers, and alleged COIN experts. Barlow wrote

the book to pertain specifically to war on the African continent, but in this

reader’s opinion, Barlow’s stripped-down language and no-nonsense approach to

what is a normally convoluted subject in military literature makes this

book worthwhile for any student of military history.

As Barlow writes in his book, “Part of the dilemma

African armies face is the continued creation of new words, terms, and phrases

to describe the same action or phenomena. This has led to a large amount of

confusion for commanders and leader in the field.” Using graphics, bullet

points, and written explanations, the author leads the reader to an

understanding about the boots-on-the-ground tactical approach, from movement

techniques and types of operations to the big picture that supports the pillars

of government. “Composite Warfare” ties them together and demonstrates how a

military campaign has to function as a mutually supporting effort that supports

the state rather than undermines it.

Comprehensive in nature, “Composite Warfare” examines

appropriate force structures, air power, reconnaissance, maneuvers, mobility,

air power, intelligence, retrograde operations, developing military strategies,

and plenty more. Barlow treats warfare in Africa with a cultural appreciation,

as opposed to a cookie-cutter, one-size-fits-all approach frequently employed

by U.S. Special Forces, who simply mirror our

own force structure in the host nation counterparts they train.

This is why the United States often trains foreign troops with tactics straight

out of the Ranger

Handbook, tactics that don’t work for indigenous forces.

In a past SOFREP interview with Barlow, he said that

“poor training, bad advice, a lack of strategy, vastly different tribal

affiliations, ethnicity, religion, languages, cultures, not understanding the

conflict and enemy,” were hallmarks of Western training provided to African

armies. “Much of this training is focused on window-dressing, but when you look

through the window, the room is empty,” he concluded.

“Composite Warfare” is recommended reading for

students of military history and strategy, including active-duty Special Forces

soldiers charged with conducting Foreign Internal Defense (FID).

Although the book will prove especially helpful to those serving

in African militaries, “Composite Warfare” will no doubt became a seminal work

on modern warfare in Africa, one practitioners and academics alike will

reference well into the decades to come. Let us hope that Barlow’s lessons are

learned and internalized, lest we repeat the same mistakes in Africa for

another half-century.